The title of this post might be a little click-baity, but it’s true. There’s one Frog and Toad story that, as a kid, I found to be a tad nightmare-inducing.

“BUT THE FROG AND TOAD STORIES ARE SO LOVELY AND BENIGN!” you shriek, your worldview crumbling around you. Well, you have obviously repressed this one.

Let me jog your memory:

Eh?

In the story “Ice Cream” from Frog and Toad All Year (1976), Toad treats himself and Frog to some delicious chocolate cones, which, on his walk back, tragically melt all over him. Blinded, disoriented, and somehow defying the laws of physics with ice cream soup draped over him like a blanket, he is mistaken for some kind of horned monster. Chaos ensues, yada yada, everything is resolved.

While the above image is objectively horrifying, it was actually not the printed version of the story that scared me. It was the printed version of the story being performed specifically in this video, by none other than Arnold Lobel himself:

I rewatched the video recently. I survived. And I reflected on what might have caused me to lodge this “terrifying” reading as an Important Memory.

First, I think my panic set in when the ice cream started melting. This frantic feeling only escalated as Lobel began reading with more and more urgency, and Toad — and I, by extension — felt completely out of control.

“Where is the path?” cried Toad. “I cannot see!”

I was also distressed by the other animals’ complete misunderstanding of the situation, which meant that no one was helping Toad when he was desperately asking for it.

And that insolent piano! It just jacked up the drama tenfold.

The illustrations were certainly a factor, too. Especially the color of the chocolate ice cream, which had a sort of grayish tint to it. I think something about this felt unnatural to me and added to the scariness.

Here’s the thing, though. The reading of this story may have disturbed me, but it did not stop me from watching it so much.

Why did I do this to myself? For the answer to that question, I look to my own children.

Apparently, my kids also enjoy self-torture

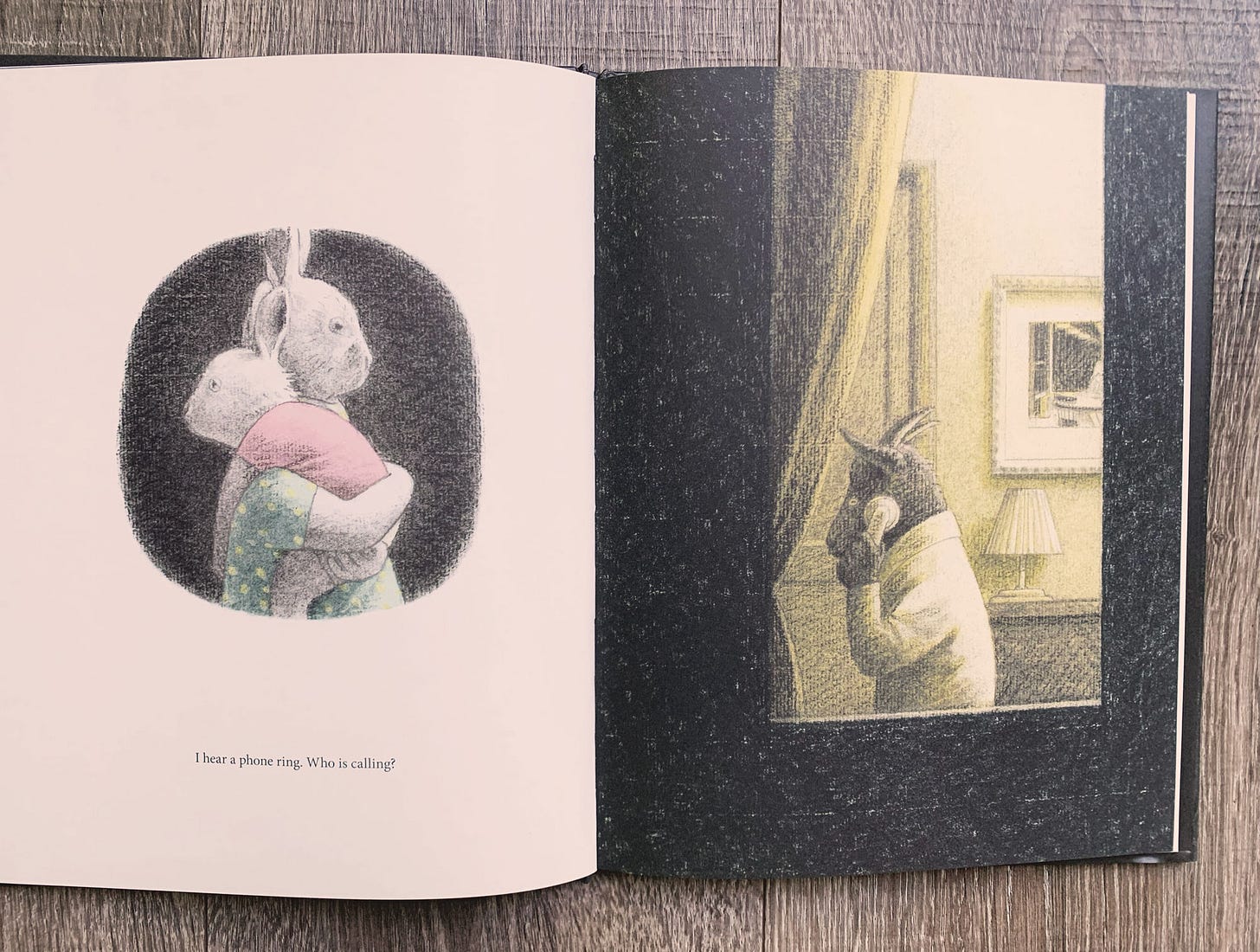

This year I read my beloved Voyage to the Bunny Planet books by Rosemary Wells with my two three-year-olds. One of the books, The Island Light, had my kids completely spellbound. Actually, it was just one page. This one:

I tried to read the rest of the story, but they savagely squealed, “NO! GO BACK TO THAT PAGE!” in unison. So we just looked at that page for a while.

Okay, what’s happening to Felix in that illustration is traumatic. He’s being held down kicking and screaming by multiple grownups while the doctor (who looks to me like he is enjoying this in a sadistic kind of way) prepares to stick a giant needle in his bum.

So, naturally, one of my kids asked if she could bring the book with her to snack time. She enjoyed her peanut butter crackers with a very nice view.

I think we can all agree that getting a shot is JUST the worst thing in the world according to kids (and many adults). So why have my children built a shrine around an image of it?

Maybe it’s a way of dealing with fears from a safe distance. Or, maybe it’s a bit novel to see something “bad” just happening to a character without the buffer of any humor, hyperbole, or fantasy element. I’m not really sure. But if my kids feel unsettled by this, they seem to like that feeling.

So is this the secret ingredient to the most captivating and enduring children’s books?

I already have an opinion about this, which is ‘probably, definitely yes.’ My favorite children’s books — the ones that have really stuck with me the most over the years — are unsettling in one way or another.

The Wind in the Willows (Kenneth Grahame, 1908) is a good example. The story is filled with beauty and tenderness and bucolic frolicking, but danger lurks around every corner. The forest is not a forgiving place. Nothing is permanent; comfort is fleeting. The through-line of the story seems to be the ruthless nature of, well, nature.

But the unease in the air — that’s the magic. It’s what makes the book such a total escape. It’s a complex, fully formed world, where light and dark coexist and anything can happen. If the story truly centered around a handful of upper-class animals (lol) doing nothing — and discontented by nothing — I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t have gotten under my skin in quite the same way.

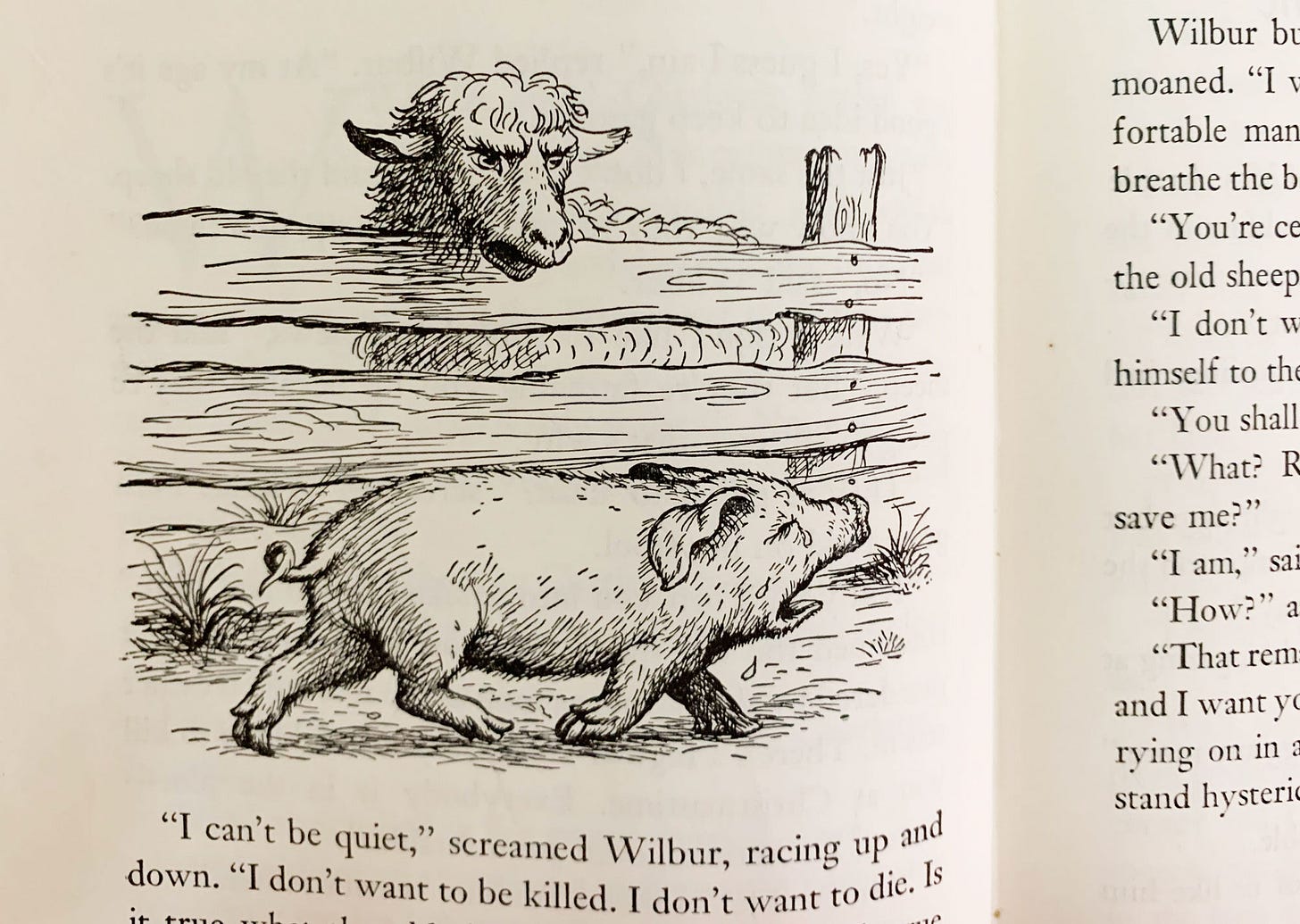

Charlotte’s Web is another childhood favorite, and to this day I find it quite unsettling. There is a certain level of emotional detachment that is necessary for those who deal with animals on a working farm, and as a kid I found this really hard to wrap my brain around. I still do, even if I can understand it on a practical level. Each animal’s fate is decided even before they’re born, and that’s just the way life is. Author E.B. White lays this reality out for the reader in full focus, never explaining it away or trying to create an idyllic alternate universe.

It is a tragedy enacted on most farms with perfect fidelity to the original script.

–“Death of a Pig” by E.B. White (1948)

(Side note: I highly recommend reading the above-quoted essay, which is both poignant and hilarious. He wrote it after his experience with a sick pig on his farm in Maine who was supposed to continue being raised for bacon, but went “up in his lines” and ended up with a conflicted White as his nurse instead, “a farcical character with an enema bag for a prop.” This was written shortly before Charlotte’s Web, and I can’t see how it didn’t directly influence the story.)

The fair ground scene at the end of the book might be the most heartbreaking thing in literature. And for me, it’s not the fact that Charlotte dies; it’s the description of the setting of her death.

Next day, as the Ferris wheel was being taken apart and the race horses were being loaded into vans and the entertainers were packing up their belongings and driving away in their trailers, Charlotte died. The Fair Grounds were soon deserted. The sheds and buildings were empty and forlorn. The infield was littered with bottles and trash.

Oops, there I am in a heap on the floor again.

That fair ground, with only ghosts of good times hanging around, has got to be the single loneliest place in the world. It’s like how the space where a party was held is somehow severely depressing to look at the day after.

White’s matter-of-factness in this scene matches that of his descriptions of farm life — Charlotte’s death is almost mentioned in passing. It’s just one of the things that happens to occur while Farmer Clyde trips on some discarded food-on-a-stick and Boodles the Clown fumbles for his keys in the parking lot. But that is life, I guess.

While this passage reduces me a puddle of a person every time I read it now, I don’t at all recall being traumatized by this book as a kid. But I definitely carried with me. And never looked at a spider quite the same way again.

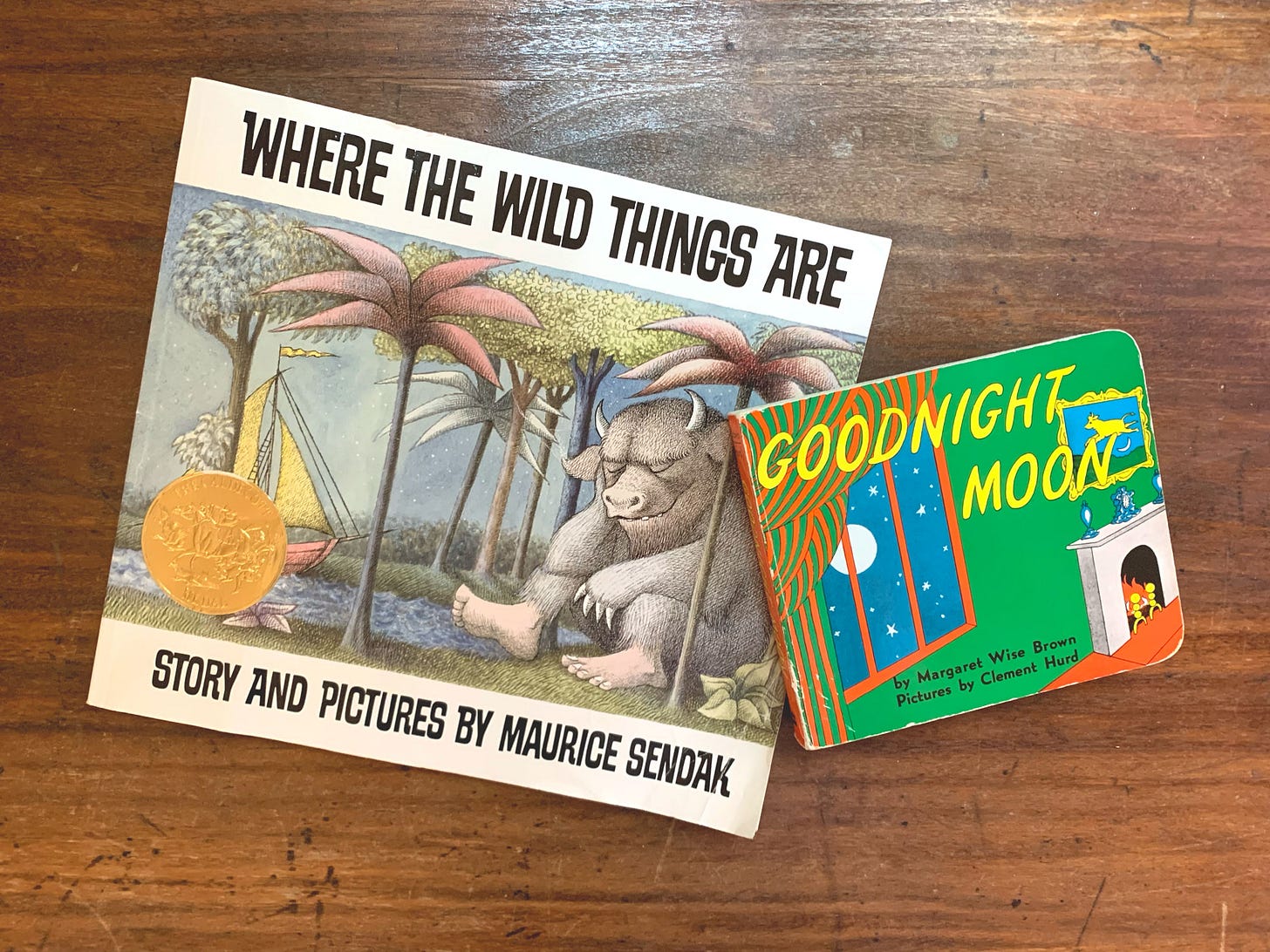

“Goodnight nobody.”

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that many of the most universally beloved picture books also happen to be unsettling in one way or another.

It’s not always the story or the words that might make us feel this way. By its very nature, a picture book’s mood is largely steered by its visuals. A single composition, lighting, or color choice has the power to tug the rug under our feet a little.

Sometimes the illustrations feel incongruent with the more sweet or straightforward story being told. Or, they’re showing us something that the words aren’t saying, which completely changes the tone of the book.

Polite words spoken by courteous hosts suddenly turn sinister.

A familiar walk home becomes more akin to a theater production, warm tableaus in the shadows revealing glimpses into others’ strange and mysterious lives.

Or an expression makes us doubt a character’s earnestness (and therefore everything the narrator has told us about them so far).

When you look up the dictionary definition of ‘unsettling’ you generally get negative connotations — disturbing, causing worry or anxiety, troubling, etc. In all of the books I’ve described, I do think we’re talking about discomfort, but the best kind. The world-expanding kind. I once saw someone describe an alternate definition of ‘unsettling’ as “delightfully disorienting.” I’m not sure I can improve on that.

Kids are in a constant state of unsettlement. They’re growing, changing, and learning at such a rapid rate, it’s impossible to be truly comfortable for very long. Maybe we’re so drawn to books that “delightfully disorient” us because they reflect this never-ending cycle of upheaval. A cycle that (much to my dismay) does not end as an adult. On a subconscious level we identify strongly with this, at all stages of our life. And that’s why these books stick with us, and we keep on reading — and sharing them.

Anyway, off to get some ice cream.

I’d love to know which book has delightfully disoriented you!

I could not get enough of sad books as a kid. I loved Owl at Home when he cried into his tea pot. And my daughter loves scary or disturbing stories and pictures. We mustn’t underestimate children, they can handle difficult feelings, and good books can help them.

Ohhhh my stars, this resonates. The one Frog and Toad that really freaks me out is The Dream when Toad keeps showing off to Frog while Frog gets smaller and smaller and smaller until he essentially disappears. Talk about existential dread.

I still get nervous when I have to share them with the littles, hoping my fear doesn’t carry over to them.

Loved this entire article!